- ໂດຍ WFsensors

Semiconductor gas sensors rely on a sensitive layer whose electrical behaviour shifts when target molecules interact with it. These MEMS devices are compact, low-cost and easy to mass-produce. To make them reliable you must control the material recipe, heater power, package gas path and the signal conditioning electronics. I’ll walk you through the engineering logic: materials and micro-heater first, then surface reactions and electrical change, after that signal readout and device classes, finishing with practical engineering tips.

ລາຍການ

1. Working Principle: Gas Detection and Surface Chemical Interaction

The basic idea is simple: the sensing material’s surface reacts with gas molecules, changing carrier density and thus the device’s electrical properties. The typical sensing layer is a metal oxide such as tin dioxide, titanium dioxide or zinc oxide. These materials sit at a baseline resistance in clean air. A tiny heater built into the chip raises the sensing layer to an operating temperature so surface adsorption and desorption can happen reversibly. That high temperature speeds up reaction kinetics and helps the sensor reset quickly between measurements. In design you must balance reaction speed, power use and lifespan so the device gives stable outputs in the intended environment. Environmental variations will shift the baseline, so systems commonly use differential measurements and baseline correction in the electronics.

1.1 — Surface Reaction Mechanism

Surface chemistry is the bridge between a chemical event and an electrical signal. Take a reducing gas as an example: oxygen from air adsorbs on the sensor surface and captures electrons, becoming negatively charged oxygen ions; this reduces free carriers and raises resistance. When a reducing gas arrives it reacts with those adsorbed oxygen ions, releasing electrons back into the semiconductor and lowering resistance. For oxidising gases the opposite happens — more electrons are taken away and resistance rises. Understanding these electron transfers and energy levels is essential for optimising doping, setting operating temperature and tuning circuit sensitivity.

2. Materials & Structure: Metal Oxides and Micro-heaters

Material choice sets sensitivity and lifespan. Metal oxides are mainstream because they’re chemically stable and straightforward to make. Different oxides react more strongly to particular gases; you can improve selectivity and response time by nanostructuring, doping or adding catalytic surface layers. Typically, a thin film or nanoparticle layer is deposited on a ceramic substrate, with a micro-heater and thermal isolation structures beneath to hold the sensing layer at 200–400°C. The package must let gas diffuse in while protecting the sensing layer from contamination or mechanical damage. MEMS scale gives quick heater response, but it also forces careful thermal management and power optimisation.

2.1 — Micro-heater Design Essentials

A micro-heater must heat quickly, hold a stable temperature and use as little power as possible. Thin-film resistive patterns or serpentine traces are common, mounted on a low thermal-conductivity support for good isolation. Closed-loop temperature control using an on-chip thermometer helps reduce drift. Even heat distribution avoids local ageing of the sensing film and improves repeatability.

3. Signal Formation & Circuit Interfaces

The electrical change in the sensing layer must be reliably turned into a usable signal. Resistive semiconductor sensors measure resistance change via bridge circuits or constant-current arrangements; the resistance shift is usually reported as a voltage or frequency change. Non-resistive types (for example, MOSFET-style sensors) detect shifts in threshold voltage or capacitance. Response time depends on reaction kinetics, diffusion depth and temperature; recovery time depends on adsorption strength and desorption rates. The readout electronics need low noise and high resolution, plus software filtering and compensation to reduce environmental interference. Practically, you must match the sensor’s dynamic behaviour to sampling strategy and filter time constants so you get both sensitivity and stability.

3.1 — From Resistance to Readable Signal

Resistance changes are commonly measured with a bridge or with a constant-current to voltage conversion. Bridge topologies can suppress temperature drift; constant-current readout is simple and linear. Detecting low concentrations requires high resolution ADCs and low-noise amplifiers. Systems also need automatic baseline adjustment to handle long-term drift, so the output remains meaningful to the host controller.

4. Type Comparison: Resistive vs Non-resistive Semiconductor Sensors

Resistive semiconductor sensors are the commercial workhorse: they’re easy to make, easy to read and very responsive to many reducing or combustible gases. Their weakness is selectivity — a single device often responds to multiple gases, making it hard to tell which is present. Non-resistive approaches (like field-effect devices) change device thresholds or other electrical parameters and sometimes give different response shapes that can aid discrimination. In practice, sensor arrays and pattern-recognition algorithms are used to overcome the limited selectivity of single devices. When choosing a sensor type you must weigh response amplitude, power draw, size and system complexity. For applications needing high discrimination, a multi-sensor array plus software models usually outperforms a single specialised sensor.

4.1 — Performance Trade-offs

Sensitivity, selectivity, stability, power consumption and cost are all in tension. Resistive devices win on cost and sensitivity, but they struggle to distinguish complex gas mixtures. Material engineering, sensor arrays and advanced signal processing can improve system performance, but they add complexity and calibration demands.

5. Temperature Control and Stability Assurance

Moving a sensor from the lab into a product requires attention to package gas paths, dust protection, moisture resistance and EMI shielding. SMD packages let you solder sensors directly to a PCB, but you must ensure the gas inlet and sensing window stay clear. Thermal management includes minimising heater power, preventing heat from coupling into nearby circuitry and keeping the sensing layer temperature uniform to avoid local ageing. Over long use, baseline drift and sensitivity loss are expected, so you’ll need calibration strategies and self-test routines. For industrial or safety use, conduct cross-sensitivity tests, temperature-humidity cycling and accelerated ageing so the outputs meet real-world trust requirements.

5.1 — Packaging and System Integration Notes

Good packaging permits gas flow while protecting the film. Micro-porous filters and designed flow channels reduce contamination; package materials must tolerate high temp and chemical exposure. Electrical interfaces should include ESD protection and signal filtering so the sensor behaves in messy electromagnetic environments.

ສະຫຼຸບ

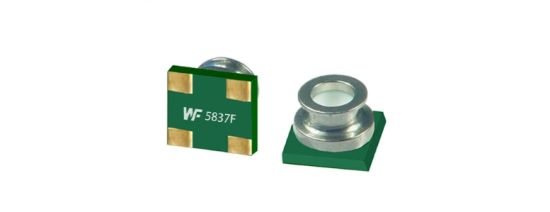

Semiconductor gas sensors as MEMS devices detect gases by reversible surface chemistry between the sensing material and target molecules, which changes electrical parameters that the electronics read out. Metal oxides are the dominant sensing material and micro-heaters set the operating temperature. Devices split broadly into resistive and non-resistive types. In engineering practice you balance sensitivity, discrimination, power and long-term stability — using material tweaks, sensor arrays, thermal control and signal processing to meet application needs. The image you provided shows a typical SMD sensor unit, handy for modular integration. Overall, this technology remains a cost-effective, high-sensitivity option for combustible gas alerts, air quality sensing and industrial safety, though reliable discrimination in mixed gases often needs a system-level approach.

The above introduction only scratches the surface of the applications of pressure sensor technology. We will continue to explore the different types of sensor elements used in various products, how they work, and their advantages and disadvantages. If you’d like more detail on what’s discussed here, you can check out the related content later in this guide. If you are pressed for time, you can also click here to download the details of this guides ຂໍ້ມູນ PDF ຜະລິດຕະພັນ PDOR Air.

For more information on other sensor technologies, please ເຂົ້າເບິ່ງຫນ້າສັນຍາລັກຂອງພວກເຮົາ.