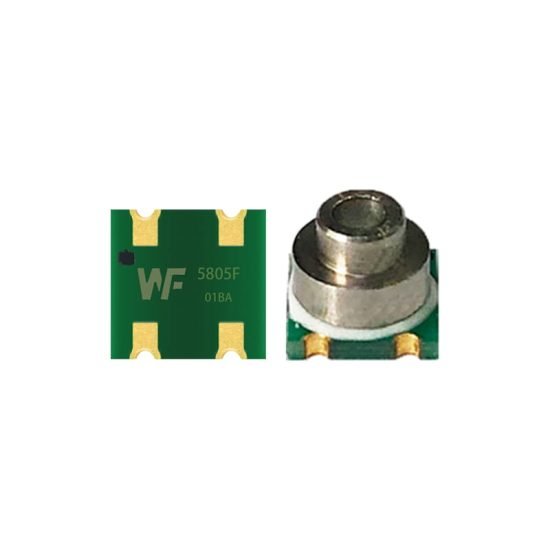

- By WFsensors

Adaptive robots need real touch. Pressure sensors—hydraulic, pneumatic, air and gas units plus tension sensors—give joints and skin real-time force feedback. Integrate compact MEMS modules , map internal pressure to torque, fuse with vision and motion data, and build low-latency control loops. The result: safer, more dexterous robots that adjust grip and motion dynamically.

Catalog

1. Tactile sensing in adaptable robots

If you want a robot to be truly adaptable, it needs a clear sense of contact and force. Cameras and inertial sensors tell a robot what it sees and how it’s moving, but only pressure feedback lets it judge the real force of contact and where that contact occurs. For industrial arms or mobile robots, built-in hydraulic sensors and thin pressure layers on the surface together reveal how actuator outputs relate to outside contact, letting the controller correct motion within a closed loop. That means the robot can handle fragile items, work alongside people, or move through tricky spaces with gentler, more precise actions.

Mapping joint and surface touch

Pressure readings at joints can be worked back to estimate torque and load distribution. That info is vital when an arm picks up or moves heavy stuff, and it can trigger protection logic the moment a collision happens. At the same time, a conformable sensing layer on the skin gives a map of where and how hard the robot is being touched, so it can tell a light touch from a knock and adjust speed and force accordingly. With the right sensor layout and bandwidth choices, you can strike a balance between motion control and safety monitoring.

2. Joint pressure enabling motion control

In many drive systems, hydraulics or pneumatics do the heavy lifting. Fitting high-precision pressure sensors into the oil or air lines lets you monitor the system in real time. Hydraulic sensors feed numbers into diagnostics for pumps and valves, and they also go straight into control algorithms to produce smooth, predictable force output. Combined with tension sensors, pressure readings help estimate the actual load at the end effector, improving control accuracy and cutting overload risk.

Proprioceptive measurements and tension estimation

Putting tension sensors on tendons, cables or load paths gives you a direct read of the pull on a component. When you combine that with internal pressure data, you get a high-accuracy picture of joint state that’s useful for closed-loop force control or force-limiting strategies. Jointing the tension and pressure reads helps spot nonlinear friction, elastic deformation and external loads, so the controller can be more robust in mixed force/position control.

3. Conformable surface sensor layers and soft shells

To get close to human touch, robots need “skin”. Conformable pressure sensor arrays can sit on flexible substrates and cover curved surfaces, joints and gaps. These sensor layers are great at detecting contact location, pressure intensity and contact duration, and they feed the controller with low-latency signals. When designing them, pay attention to unit density, sensitivity and noise rejection so the data stays stable in complex scenes.

High-resolution pressure array design

Arrays give spatial resolution but raise data volume and wiring complexity. A common approach is local pre-processing and compression: do simple filtering and thresholding in the skin layer, then pass summary data to the main controller. That keeps tactile detail where it matters and lightens the central compute load. Electrical packaging, moisture protection and mechanical durability are just as important — they determine how reliable the system is in long-term collaborative use.

4. Monitoring internal fluid/air systems

The pneumatic and hydraulic lines inside a robot carry the energy that drives motion and gripping. By placing absolute or differential pressure sensors in key circuits, you can spot leaks, blockages or pump efficiency loss straight away. Air and gas sensors also help detect environmental pressure shifts or ingress from water — crucial for outdoor robots or systems needing high ingress protection. Continuous internal pressure monitoring turns looming failures into maintainable signals, preventing catastrophic breakdowns.

Pressure signals for leaks, flow and altitude

Differential pressure measurement can reflect flow changes and even be used to estimate altitude or airtightness. When you analyse differential pressure together with other sensor data, you can tell whether a fluctuation comes from a load change or a system fault, and pick a conservative or aggressive response. Robust sensors and sound thresholding give you earlier maintenance windows and higher uptime.

5. Data handling, control and learning loops

Pressure sensing is only part of perception — its real value is how the control system reads it and acts on it. Modern control tends to fuse pressure with vision, inertial and position data for sturdier action decisions. Machine learning models can take real-time pressure maps from arrays and optimise behaviour; for example, pressure-based inputs have been used in reinforcement learning to teach arms delicate manipulation like rolling a ball across the palm. In real deployments you must balance model complexity against real-time needs so the system stays safe under limited compute.

From pressure to motion: control loop design

The key to closing the loop from pressure reads to motion adjustments is a low-latency data path and clear control goals. Simple PID control handles most contact tasks, but for high dexterity you’ll want prediction models and adaptive gains. The system should distinguish routine contact from sudden impacts and switch control modes accordingly, so it completes tasks while protecting human partners.

Design and engineering considerations

Pick sensors whose media compatibility, range, bandwidth and package match the use case. Hydraulic circuits need high-pressure sensors; skin layers and air lines need low-drift, high-sensitivity micro-units.

Lay out sensors to balance redundancy and latency. Critical actuators should have dual channels for fault tolerance.

Design the signal chain (sampling, filtering, scaling) in both hardware and firmware so low-frequency events aren’t missed and high-frequency noise doesn’t cause control jitter.

Environmental protection (dust/water resistance) and mechanical durability are essential, especially for outdoor or rescue robots.

Conclusion

Pressure sensors supply internal and external force data that can’t be replaced if you want more adaptable robots. Layer hydraulic sensors, pneumatic/air/gas sensors and tension sensors by function, and fuse their readings through appropriate processing and control strategies — the result is a robot that’s safer, more dexterous and more reliable. Robots that rely on pressure feedback are better at working shoulder-to-shoulder with people, handling unknown disturbances and carrying out complex tasks in the physical world.

The above introduction only scratches the surface of the applications of pressure sensor technology. We will continue to explore the different types of sensor elements used in various products, how they work, and their advantages and disadvantages. If you’d like more detail on what’s discussed here, you can check out the related content later in this guide. If you are pressed for time, you can also click here to download the details of this guides air pressure sensor product PDF data.

For more information on other sensor technologies, please visit our sensors page.